The REFUGEES

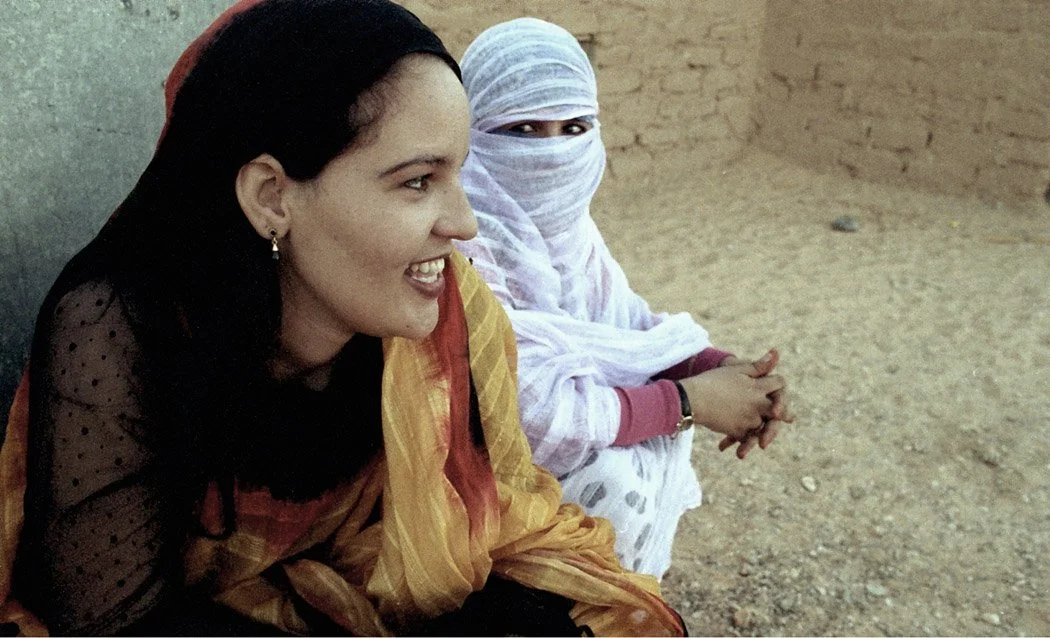

"What is it to be a refugee? Who are we? We know we are Saharawis, but only we know. The world does not know we exist. Being a refugee is like being outside this world."

– Fatimetu Shagaf, born in the refugee camps

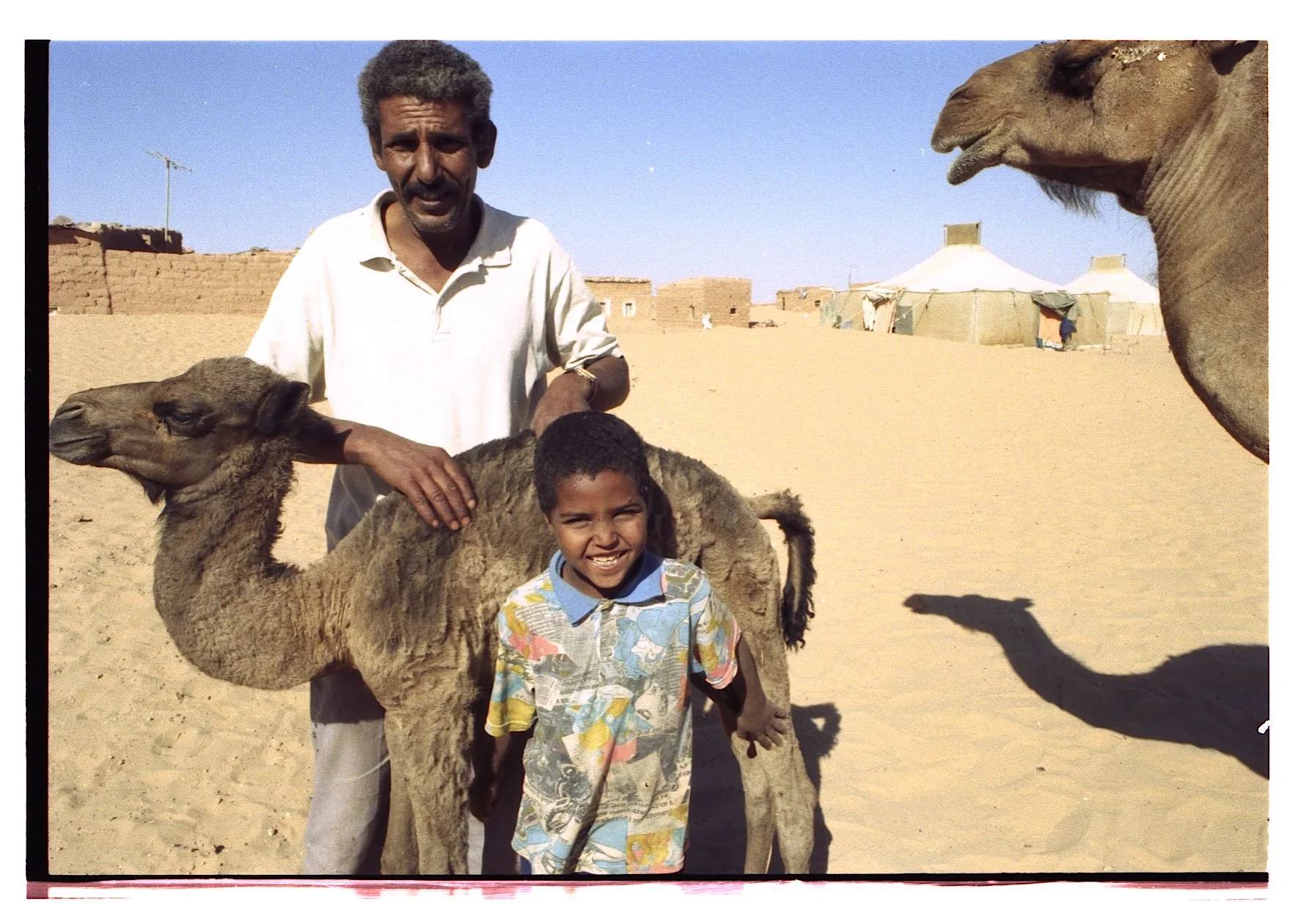

According to the latest UNHCR report of 2018 there are 173, 600 Saharawi refugees living in one of the most hostile desert environments in the world – known as the Hamada, in SW Algeria, where there is almost no rain, no vegetation and temperatures are extreme, soaring above 50°C in summer and dipping below freezing in winter. Most health issues suffered by the refugees are related to the extreme environment of which 80% of the population are are women and children.

Nearly 50 years since the Saharawis were displaced to this barren region, they are still largely dependent on precarious flows of international aid to meet their basic needs. Today, a third generation are growing up with few prospects for a better future and have limited access to quality education locally.

Photo by Olivia Mann

How the Saharawis Became Refugees

The events triggered by the Moroccan and Mauritanian invasions of Western Sahara at the end of 1975 are directly linked to the large displacement of the Saharawi population.

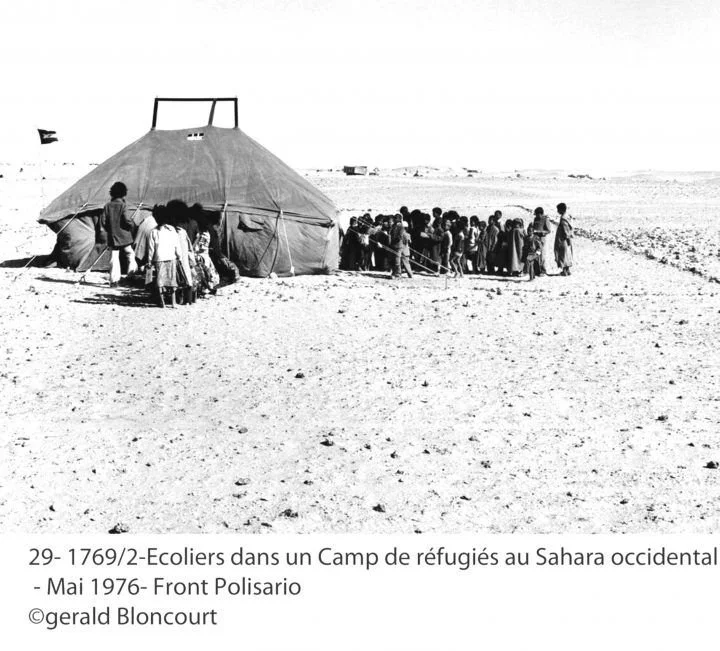

The majority of Saharawis became refugees after Moroccan planes bombed civilians in temporary camps in the interior of Western Sahara with banned napalm and cluster bombs in the early months of 1976.

Photo by Gerard Bloncourt from @saharawihistory

The Polisario liberation movement, unable to protect the civilians and fearing genocide, was able to secure Algerian support who offered the fleeing Saharawis a relatively safe haven in the southwestern desert region near Tindouf. Accounts from Saharawis who remember the early days of refugee life tell of enormous hardships. They arrived, many by foot, to a bleak, barren desert patch, traumatized, exhausted and with virtually no possessions. Epidemics and near-starvation was rife.

The next Saharawi exodus, although on a smaller scale, took place in 1979 when Mauritania withdrew from the conflict and Morocco annexed the rest of Western Sahara.

According to the Saharawi Red Crescent, apart from individual cases of Saharawis successfully escaping the repressive Moroccan occupation, there has been relatively little forced population movement since 1979. Ironically, fear of Moroccan infiltrators and spies has meant that Saharawis newly joining the camps have often been initially treated with suspicion and hostility.

The Refugee Camps

The Saharawi refugees are spread out between five large camps called wilayas (provinces). Each wilaya is named after a main town in Western Sahara: Laayoune, Ausserd, Boujdour, Smara, and Dakhla. A wilaya is divided into six or seven dairas (boroughs), also named after places in Western Sahara. These dairas are further subdivided into four smaller neighbourhoods known as hays. The camps are located at various distances from the nearest Algerian town of Tindouf, the closest one of Laayoune being 20 minutes away by car and the furtherest one of Dakhla being 2 hours away.

"She always cried a lot and it made me cry too. She told me how everyone was screaming, and how she saw babies being burned, [and] women losing their feet and hands as they ran."

– Nanaha Bachri, recalling her late grandmother's relation of this tale

Photo by Diko Betancourt

Every daira has its own primary school, health clinic, and administration. Between 2,000 and 8,000 refugees live in a daira. Nowadays, most of the wilayas also have middle school for children to study up to 9th grade, but after that they must leave the camps to carry on their studies.

The Saharawi refugee camps provide a temporary base for the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), the Saharawi government-in-exile, which is full member state of the African Union. In the camps there are 19 ministries, 3 of which are headed by women. 23% of elected members of parliament are also women. The government is located in Rabouni, the administrative centre of the camps where the Parliament and their national SADR TV and radio stations are also based.

Photo by Danielle Smith

Photo | Olive Branch Arts

EDUCATION Preparing for Independence

Still, despite these remarkable achievements, the stark truth remains that the Saharawi refugees have few opportunities to apply their degrees in the camps and unemployment hovers around 80%. They are a vulnerable, aid-dependent population with extremely limited possibilities for young educated adults to develop professionally and find meaningful work.

The Role of Saharawi Women

With most of the men away fighting at the warfront for 16 years until 1991, it was the women who were primarily responsible for building the camps from nothing and running every aspect of life. They showed huge determination and resourcefulness. Many of the large tasks were organised in the spirit of Twiza, the expression of the communal spirit and belief in the coming together of many hands to lighten the burden.

Over the past decades, and with huge determination and resourcefulness, the Saharawis have managed to lay the foundations of a state-in-exile. Aid agencies and NGOs provide vital assistance, but it is the Saharawis themselves who run the camps. In fact, they see themselves as much as citizens of a nascent state as refugees, with their own government. The self-proclaimed Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic,celebrated every year since February 27 1976, is a full member state of the Africa Union and at various points has been recognized by over 80 countries worldwide.

A remarkable side of the refugee story has been the huge advances made in raising the educational level of the population. Less than 10% were literate in 1975, whereas now that level is over 90%. Women in particular have made impressive strides, with graduates in the fields of law, engineering, economics, medicine and diplomacy.

Education since the onset of the struggle has been seen as integral to achieving true independence. Despite overwhelming challenges and the lack of resources, the Saharawi leadership has always made the education of the Saharawi refugees a priority. It is free and universal and huge efforts have been made to secure sponsorship for their youth to gain higher education and university degrees outside the camps. Cuba, Libya and Algeria have played a major role over the years in providing this vital higher education sponsorship.

Photo by Danielle Smith

In 2009, then-President of the Saharawi Republic, Mohamed Abdelaziz, signed a decree ordering the establishment of the University of Tifariti in the oasis town in the "liberated territories" controlled by the Polisario.

Moroccan bomb shelling in 1976 forced residents of Tifariti to evacuate, and the heavy attacks continued until the ceasefire agreement in 1991. The Polisario began reconstructing the ghost town in 1991, and it is now the only permanent settlement in this part of Western Sahara. With a population of around 3,000 people, Tifariti also has a hospital, a school, and a museum.

Photo by Danielle Smith

The University of Tifariti has so far been able to attract 450 undergraduate students and almost 90 academics. It hosts four University Centres: the School of Nursing, the School of Administration and Computer Science, the Pedagogical Institute of Teachers and Professors, and the Institute of Information and Journalism. The Faculty of Law is also planned and will be established soon.

Photo by Danielle Smith

"Arrived yesterday, become a shepherd today"

– Saharawi proverb